This piece is primarily concerned with determining if an exploration campaign is worth pursuing. The concept is explored through the particulars of the copper market and BHP’s control of South Australian production, its speculated expansion plans and the IOCG (Iron-Oxide-Copper-Gold) deposit types metallurgical characteristics.

In other pieces I have speculated as to the ability to predict a discovery, here we attempt to examine a belt of significant mineralization and speculate on what a significant value enhancing discovery would look like. This is an exercise I have gone through previously as an explorer and defines something that is severely lacking in the industry. Exploration targets are often defined through their chance of existing and ease of discovery but are rarely considered in the context of an exit strategy.

Grade vs tonnage plot showing Porphyry and IOCG deposits (IRON OXIDE COPPER-GOLD ( ± AG ± NB ± P ± REE ± U ) DEPOSITS : A CANADIAN PERSPECTIVE). Low-grade, low-tonnage deposits are rarely economic whereas large tonnage, high-grade deposits tend to be highly economic and desirable, these should be the targets of exploration.

As explorers we work for the shareholder and technical successes are not enough, they have to take the shortest most efficient path to shareholder returns. As a result, we must assess if the targets we are pursuing are something that can be sold or developed into a mine. If they are small and in-line with the undeveloped heap of sub economic projects previously discovered, then we are not serving the shareholder and our funds are better used elsewhere.

We use South Australia as an example and attempt to imagine what a deposit would need to look like for us to have a ready buyer in BHP.

Growth priorities

For anyone paying attention it is self-evident that copper has become a top strategic priority for many of the world’s major miners. Whether it is Barrick deciding to pursue developing Reko Diq in Pakistan, Newmont becoming a Gold-Copper company by ingesting Newcrest (Gold miner Newmont to sell assets, cut jobs after Newcrest buy) or BHP buying out Oz minerals (Completion of OZ Minerals acquisition) and attempting to do the same to Anglo American, copper has definitely become a key battle ground.

Reko Diq deposit location

Anglo American managed to survive and hold onto its juicy interests in the big porphyry mines of Collahuasi, El Soldado, Los Bronces and Quellavaco. These four with the inclusion of the small but high grade Sakkati deposit contain just over 91 million tons of contained copper (Ore Reserves and Mineral Resources Report 2023) in inferred resources at very respectable grades for open pit porphyries. Moreover, the inflationary environment and significant social and technical risks associated with developing new projects has made buying mines much more appealing than building them, something gold miners have been experiencing for several years.

Things haven’t slowed down on various development fronts either, Newmont no doubt wants to set up a block cave at Red Chris given the appealing economics (Red Chris Block Cave Pre-Feasibility Study confirms Tier 1 potential), the land swap deal continues at Resolution (US court approves land swap for Rio’s Arizona copper mine) and Oak Dam is getting a double decline (Oak Dam Underground Access Project) (along with a development drilling level and a double raise, clearly intended to serve as mining infrastructure after the drill out). Lots of copper is promised to come online at some point in the future to supply projected demand.

Oak Dam underground infrastructure for ongoing mining studies.

The regions that host these deposits are expected to make the greatest contribution to copper supply increases i.e. BC’s Golden Triangle and SW US, Andes, Olympic Copper gold province of South Australia and the Central African copper belt. Deposits in the former feature much less prominently in the majors’ portfolios but have seen significant Chinese investment.

Each has its challenges, in Africa it is political, in the Andes, water and high-sulphidation overprints (depositing arsenic and other junk) and in South Australia it is sterile unmineralized cover, water and radionuclides. Notwithstanding the political problems that I have no intention of dissecting and what should be the obvious observation that deserts are generally devoid of large amounts of water the other issues relate primarily to metallurgy and concentrate quality.

Concentrate quality

Before we proceed to dissect this issue in its entirety it is important to explain why concentrate quality matters. Most mines do not produce a finished product that can be marketed to manufacturers, they produce a concentrate (First Shipment) that is processed at 3rd party smelters.

Copper concentrates from the Kanmantoo deposit being loaded into a bulk carrier.

Here it is smelted to recover the main constituent element and any by products that can be economically extracted. In the case of the copper mines mentioned the main product would be Copper and the by-products Au, Ag, Co, Te, Se, Pd etc depending on that particular mines ore makeup. In addition to the desirable elements that come through, many undesirable elements i.e. As, Bi, Mg, Hg can also be present in the concentrate and need to be managed. For example, Bi can reduce the final quality of copper by making it brittle and unsuitable for wiring, Mg can produce dangerous accumulations in the smelter’s chimneys and As can increase the cost of production by creating more work and leaving the smelter with what is in effect a toxic waste. Therefore, the cleaner the concentrate that a mine produces the more they will get from the smelters. This has become such an issue in the past two decades that significant efforts have been invested in ameliorating the problem. Solutions such as additional metallurgical processing steps (German-Chilean consortium investigates new ways of reducing arsenic in copper concentrates) (Codelco Arsenic Strategy ), new technologies (Trends and Treatment of Impurities In Copper mining) and perhaps most simply blending yards (Glencore starts copper concentrates blending facility in Taiwan) have popped up in many locations. Here dirty concentrates from one part of the world meet clean concentrates from elsewhere and leave as blends containing deleterious elements at concentrations below all smelter penalty levels.

This has certainly reduced the impact of complex concentrates and meant that high-As concentrate producers when operated alongside other cleaner operations have managed to get more for their product then they otherwise would have. There is nothing new to concentrate trading and blending but with more complex material entering the market it has become a much larger issue to manage. So much for high-As concentrates associated with Andean Porphyry deposits, but what about South Australia’s Iron-Oxide-Copper-Gold (IOCG) deposits?

Hot concentrates

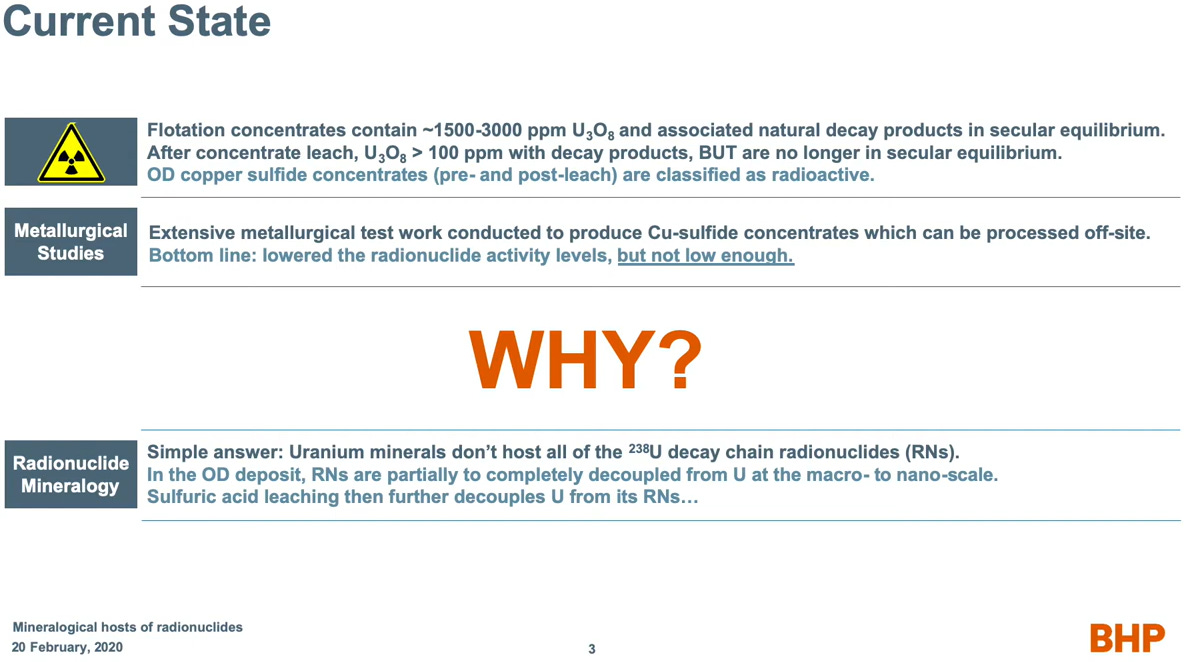

Here the problems become much more complex. For an excellent in-depth view, I recommend this fantastic presentation from Dr. Kathy Ehrig.

As a quick explanation, IOCG’s in South Australian deposits contain elevated concentrations of uranium, so much so that Olympic Dam contains 30-50 % of the worlds known U-resources. Additionally, all the other IOCG deposits in the state such as Prominent Hill, Oak Dam, Hillside and Carrapateena all contain elevated uranium with a early resource at Carrapateena containing 0.27 kg/t U3O8.

Olympic Dam concentrate classification taken from the video above.

Suffice it to say uranium in copper concentrates is undesirable and most global smelters will start penalizing anything above 10 ppm U3O8. As a result, Olympic Dam leaches the Uranium out of both its concentrates and tailings while the other mines operate cleaning circuits to remove as much of it as possible.

Simplified Olympic Dam processing flow taken from (Olympic Dam – is it really complex?). Note the Cu concentrate leach.

In the case of Prominent Hill and its comparatively low U-concentrations this worked, and a sellable concentrate was produced. The same goes for Carrapateena. However, at Olympic Dam the resultant concentrates were too hot to ship owing not to the uranium but to the daughter products present that could not be removed in the concentrate leach. As uranium decays, it does not immediately transform into stable Pb but rather goes through a series of steps (known as the decay chain), each of which can be remobilized into minerals that can stay with the copper concentrate during processing. Thus, removing the uranium does not remove the radioactivity completely.

Uranium 238 decay chain

Olympic Dam radioactivity throughout the various processing steps, note the concentrate leach removes much of the radioactivity but the daughter product radioactivity remains.

This is why BHP is forced to run a copper smelter in the middle of nowhere with some of the highest power and gas prices anywhere in the world. As a concentrate what Olympic Dam produces is classified as a radioactive material. Prior to being acquired by BHP, Prominent Hill and Carrapateena would have needed to manage the more uranium rich parts of their deposits carefully so as not to exceed thresholds of acceptability but now these concentrates along with additional production that will come on-stream from Oak Dam can be leached in the same way as Olympic Dam cons are. If they are still too “hot” then they can go to the smelter.

Ultimately, this will place demands on the Olympic Dam processing circuit, and exactly how much excess capacity exist out there is not clear but sufficed to say its likely not double or triple what Olympic Dam is putting out. As a result, capital costs associated with what looks like the big expansion in South Australian copper production (BHP: Copper is king - Australian Mining) may require a smelter expansion or a new smelter. If this is indeed the case it is a significant additional capital cost and an ongoing operational cost that if it did not exist would make South Australian copper even more appealing.

So, what has this all got to do with selling an orebody to BHP? Very simply, if an additional deposit in South Australia was discovered, that had appealing economics, was large enough and critically contained little to no uranium and other radionuclides, BHP could blend the concentrates from some and possibly all the deposits to a mix that could be exported. This would therefore reduce the OPEX and CAPEX costs involved in the expansion of South Australian Copper production and deliver value greater than just the contained metals. Ideally, we would want to have it be somewhere close to the existing operations to avoid excessive trucking, we would want it to be profitable as a standalone operation and it would have to have size.

Existing resources

South Australia already contains other copper mines and deposits that do not share the high uranium and other radionuclide concentrations. Namely, the recently restarted Kanmantoo operations, along with deposits belonging to Havilah Resources (Kalkaroo) and Coda Minerals ( Emmie Bluff). BHP inherited an option to mine the Kalkaroo deposit with Havilah from the Oz Minerals acquisition but recently, decided not to pursue it (Havilah-BHP alliance to end). Coda’s Emmie Bluff deposit on the other hand is only 16 km south of Oak Dam so from a logistic point of view is interesting. However, it is unclear if BHP has any interest in this orebody. Generally, BHP and other large miners like to buy and develop very large high-grade deposits.

The ideal deposit and prudent exploration target

If we work off the assumption that BHP is backing the Olympic Copper province, and that significant value can be unlocked by developing a large clean concentrate operation alongside the variably uranium mineralized deposits and development options, then we can define our exportation target in terms of what BHP would happily buy. The checklist would look something like the table below:

When we look at the numbers provided, we immediately come to the same conclusion BHP did with respect to the deposits owned by Havilah and by extension Coda. They are not large enough or high-grade enough to move the dial and be Tier 1-2 level operations as defined by Richard Shodde. The numbers provided are what the author considers the bare minimum and as a result an exploration strategy being pitched to find less should be treated with contempt. A strategy proposing to pursue targets that can deliver deposits of the size and characteristics given, or larger can then be given further consideration.

What are these targets and who is chasing them?

Given that all the existing IOCG deposits in South Australia carry at least some Uranium, in the search for non-radiogenic concentrate producing orebodies, we need to look at different existing or speculative forms of mineralization. Several such examples have been demonstrated in the state and proximally to the operating mines. Namely, these are:

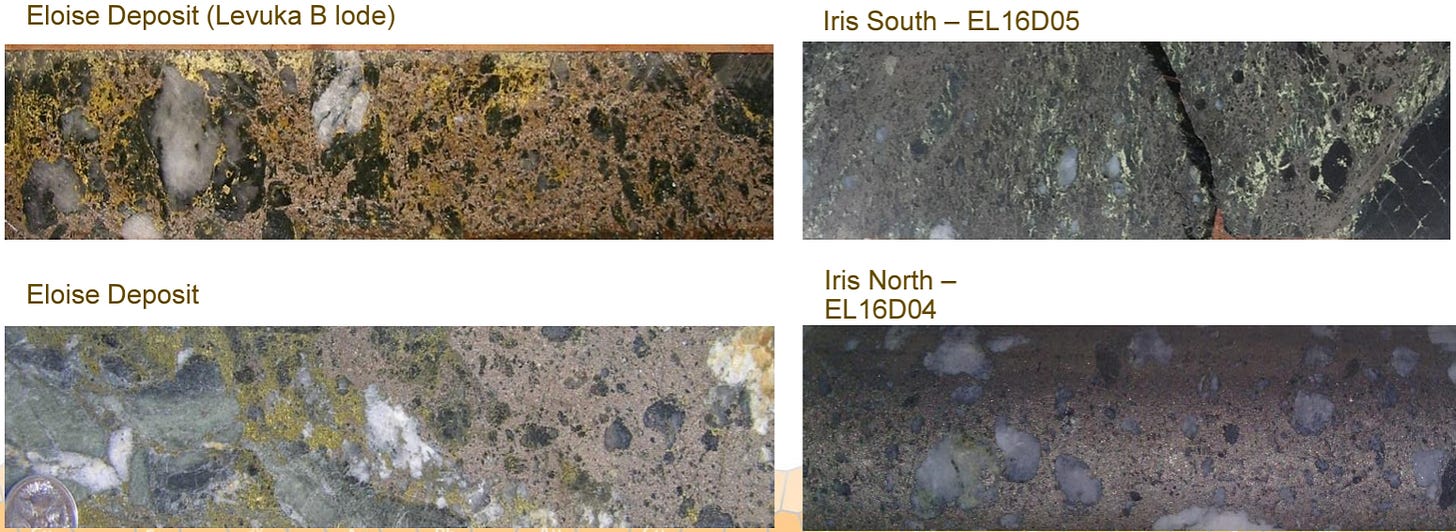

1) Iron-Sulphide-Copper-Gold (ISCG) mineralization (akin to the Jericho deposit in Queensland)

There are several demonstrated intersections that came to fruition as a result of the short-lived Minotaur-Oz Minerals exploration alliance (OZ Minerals and Minotaur collaborate on SA copper search). The Rationale to look for this type of mineralisation in South Australia came off the back of Minoraur’s discovery of several small prospects of this type and the recognition that IOCG terrains could contain high grade structurally controlled chalcopyrite-pyrrhotite mineralisation. The collection of ground EM data across significant tracks of ground near Prominent Hill resulted in some interesting intersections but nothing big enough to justify ongoing exploration. Moreover, given that Jericho (or perhaps Eloise) is the largest known of these deposits, this deposit type is unlikely to host enough tons to interest our buyers. The exploration rationale and deposit details are recounted beautifully here by Tony Belperio (Exploration for IOCG and ISCG copper-gold giants: How different could they be?). It is relevant to note here that Belperio was part of the teams that discovered both Prominent Hill and Jericho.

ISCG mineralisation examples from the Mt Isa inlier. Note the abundance of the iron sulphide pyrrhotite accompanying the chalcopyrite and the absence of iron-oxides characteristic of IOCG deposits.

2) Sedimentary copper mineralization (as per Coda’s Emmie Bluff resource)

Coda’s Emmie Bluff constitutes this type of mineralisation. However, the Central African Copper belt contains examples that are much more impressive. The Kupffer Schifer of Germany/Poland constitutes this type of ore as well. Perhaps the most impressive example a sedimentary copper deposit is Kamoa-Kakula.

The two deposits constitute a highly improbable mixture of size and grade. Due to these characteristics a hypothetical sedimentary Copper deposit has the potential to fulfill the characteristics of something BHP would buy. In the area of Emmie Bluff, occurrence of this mineralisation appears to be concentrated to a fault bound block of Tapley Hill formation (stratigraphic host) that is otherwise absent from the surrounding area. Of great interest regionally is IGO’s Copper Coast (COPPER COAST PROJECT TECHNICAL OVERVIEW) exploration project which occupies the upper reaches of the gulf. Exploration updates have been sparse here, but the company has claimed to have identified prospective stratigraphy in historical drillholes.

3) Cloncurry type IOCG (as per Earnest Henry in Queensland)

Finally, and of greatest interest to your author (I hold shares in ASX:CUS) is the prospect of further IOCG mineralisation north of Olympic Dam in the Peake and Denison terrain. Unlike the IOCG deposits of South Australia, uranium, despite being present in the likes of Earnest Henry is at such concentrations that it is not an issue as evidenced by Evolutions statements ( Ernest Henry Mineral Resource Material Information Summary).

Evolution experience no issues associated with radionuclides in concentrates from Earnest Henry.

The Peake and Dension terrains main thermal and mineralizing events overlap much more closely the ages observed for IOCG mineralisation in the Mt Isa inlier than they do the remainder of South Australia’s IOCG. On this basis in can be speculated that such a system if in existence in the Peake and Denison inlier will contain low uranium in-line with Earnest Henry.

Tony Belperio and the team at Minoraur Exploration after discovering Prominent Hill and Jericho moved on this terrain through a short-lived company called DeMetallica Resources that came about through the merger of Andromeda and Minotaur’s kaolinite assets. A vehicle was needed for the Jericho deposit and the other Queensland and South Australian copper exploration tenements. DeMetallica quickly struck up a farm-in deal with Oz minerals and this led to a couple of technical successes where “Earnest Henry type” mineralization was discovered (Wills and Mawson visuals, Assays) and never followed up as a result of AIC mines buying DeMetallica and BHP buying OZ Minerals. In reality no one has it top of mind to follow these up.

Heavily altered and mineralized drillcore from the Wills prospect, now owned by AIC mines with a BHP farm-in agreement

However, on an adjoining block of tenements Copper Search, also featuring Tony Belperio along with other industry veterans has been conducting diligent systematic (and expensive) exploration for a number of years. At this point they have a couple of targets that are about as good looking as they can be, and one gets the impression that should these come up duds the company will go look at something else for a while. This is not to say that they are bad targets, and no others are present but eventually everybody runs out of ideas after drilling many holes with only technical successes to show for it in-line with DeMetallica’s efforts.

The targets pursued, Douglas Creek and Paradise Dam both have significant scale and the means by which they were delineated can be seen here:

Ultimately, the chance of either of these turning up an orebody are extremely low, but should the drilling manifest one of significant size, grade and lacking radionuclides, ready buyers will abound. If not BHP then someone else will have the good sense to develop the project and sell the concentrates to them. But there is a lot of if’s and could’s between now and then.

The two targets being drilled are centered on the Karari shear zone and its intersection with secondary structures.

The Paradise Dam target is extremely large and intense IP chargeability anomaly tracking a Proterozoic aged NW structure. The company speculates that the chargeability anomaly is caused by copper sulphide minerals.

Conclusions

This article was written as a detailed means of exploring exploration targeting from the perspective of maximizing shareholder value and providing a rapid valuable exit. In reality despite one’s best intentions exploration rarely works out ideally. For example, the outcomes in the case examined are most likely the discovery of nothing or of another sub-economic deposit. As a great outcome, one could imagine the discovery of a IOCG in-line with exiting deposits from the perspective of radionuclides. BHP may want to buy this but in the grand scheme of South Australian copper development there would be no incentive to do it quickly, the same CAPEX investments would need to be made.

The very best-case scenario of a clean Tier 1 discovery near existing operations is almost a pipe dream but pursuing an exploration strategy that as an outcome aims to deliver another sub-economic deposit is guaranteed to fail, whereas the former at least has some hope of success.

Finally, a repeat of the disclaimer, nothing here is financial advice, comes with no warranty and I take no responsibility for anyone’s financial decisions.

Cheers,

CC

Impressive coverage of current status of S.A. search space.

Edit: Should be Minotaur "OZ Minerals and Havilah collaborate on SA copper search"